28 weeks and counting: Exercise and my Independence

Mum: The Headmaster of your junior school, in Handforth, near Manchester, was an enthusiastic walker. He made weekly group walks for families of the pupils a feature of the School’s activities. The beautiful country in and around the nearby Peak District made it the ideal location. Each weekend, the Headmaster, Mr Bonner, gave out a sheet of instructions for the walk, which usually covered a circular course of six to eight miles. We were keen participants. Each Sunday, we would pack our rucksacks with sandwich and fruit lunches, thermos flasks of coffee and tea and, most importantly snacks of chocolate and Kendall Mint Cake to keep up our energy levels, and set off in our car to the meeting point for the start of the walk. We were doing the walks regularly in the period before your diagnosis and I wonder whether, for a time, the strenuous activity may have meant that you exercised off all the build-up of glucose and ketones every Sunday and that postponed the recognition of the severity of your condition. The time came when your body couldn’t cope any more and the onset then came suddenly. Your collapse that led to your diagnosis was on a Sunday, when you would normally have been on a day’s hike.

We did not resume the School’s group walks after your diagnosis. We felt we needed time to adjust to the new situation and the School’s programme would not have given us the flexibility to adjust the lengths of the walks and take the breaks we needed. By the time we would have been ready to rejoin, you had moved to a new school. However, we did some family walks from time to time. And, once we had settled into a routine post diagnosis, I know I felt very strongly that, if I took what precautions I could, you needed to be free to do things.

Me: I am very grateful that independence was encouraged and I was neither prevented from doing activities nor subjected to excessive parental supervision. When parents know the risks – particularly concerns surrounding hypoglycemia¹ (hypos) and the ability of a child to deal with these episodes when out and unsupervised - it must be hard to let go. However, I was actively encouraged to get out of the house and either meet up with friends who lived on the same housing estate or take part in more organised sports. Mum bought a small yellow enamel box that was just large enough to hold glucose tablets for treating a hypo and had a chain attached to it. I wore this around my neck wherever I went to ensure that I always had a glucose supply with me. My parents also took out Medic Alert Foundation membership for me and, from diagnosis, I have worn a medic alert bracelet on my wrist to alert anyone to the condition, should I be unable to speak for myself in a medical emergency.

I am not aware of having been given any specific advice on how to manage different sports, length of play or varying levels of exertion. On one or even two injections a day, you could not reduce your insulin dose to cope with changing activity levels. Without the home blood glucose monitoring or CGM traces, that are available today, you could not see the impact of different activities on blood glucose levels, so you were unable to predict when your blood sugar was likely to be falling, when to eat glucose tablets to prevent or treat hypos and then whether what you had eaten was sufficient to enable you to resume activities, confident that the hypo would no longer affect performance. By the time I felt the symptoms of a hypo, it was likely that my blood glucose had been low for some time. Knowing no better, if I felt I had a low blood glucose level, I would eat and carry on.

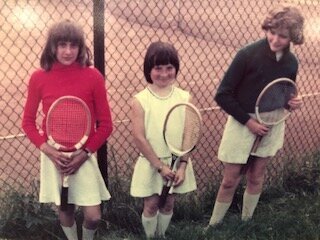

I was a keen tennis player and had a great rivalry with a friend and close neighbour, Clare Emery. Her father was a coach at the local tennis club, which was a short walk from our houses. We would spend regular Saturday mornings at the club, playing friendly matches against each other. I had an additional supply of glucose tablets, kept in my tennis racquet cover, to eat when needed. They would be slightly yellowed, hard and rather unappetising, as a result of prolonged exposure to the air from being stored this way. I would often wait to treat hypos until I felt I had no alternative, because I disliked these discoloured glucose tablets so much.

With tennis, I would realise my blood sugar levels were too low when I was becoming clumsy with my hitting or feeling overwhelmingly angry at my inability to play in the way that I was capable of doing. On one occasion, when I was eating glucose tablets between points, a boy standing outside the court watching us with some friends asked me what I was doing. I explained that I was eating sugar to treat a low blood sugar level. I remember feeling furious that he said I couldn’t be a type 1 diabetic because his mother was a diabetic and she wasn’t allowed to play sport.

I believe I had some sort of awareness of the difficulties that type 1 caused for me in sport and, more importantly, I felt an underlying sense of frustration about them. The tennis club had an annual tournament and, invariably, Clare and I always seemed to be the ones playing each other in the final for our age category. I always came second to Clare. Results from our Saturday games throughout the year tended to be fairly evenly matched but I could never beat her at the annual tennis tournament. Maybe I would not have done so anyway, but no special glucose replenishment arrangements were made before the matches in the tournament and I wonder now whether that might have made a difference. I did not understand the physical impact that different levels of exertion had on me - I am not sure that anyone really did in the early 1970s - but I remember episodes of growing anger and frustration on occasions when my body seemed incapable of responding in the way that I wanted it to.

My lack of ability to fully understand or express this, and the moods that followed, often resulted in my being called a bad loser, if I allowed my feelings to show to close family. For a long time, I found this very difficult to handle. I was always competitive and wanted to do well but my moodiness was not simply down to an immature response to losing. It was often a reaction to feeling trapped in a body that did not respond the way I wanted it to.

I was always keen to try new sports. I wonder whether it was my subconscious attempt to find something that I felt I could participate in, without type 1 getting in the way. After a day visiting Altrincham Ice Rink with family friends, I fell in love with ice skating. I somehow managed to persuade my parents to sign me up to lessons and Mum would drive me over to Altrincham twice a week. I loved the speed and sense of freedom on the ice but despite a snack before skating, type 1 continued to be able to cause unpredictable hypos. Clumsiness and a greater tendency to fall over when attempting jumps, would alert me to blood sugar falls. I remember a particular session when I fell heavily after a lesson, whilst practising techniques learnt that day. It was a stupid error and I fell heavily on the ice, winding myself. My teacher saw and skated over to help pick me up. I went off the ice to get my breath back and eat another snack. The episode left me feeling quite shaken but I remember his encouraging me to get back onto the ice. I must pick myself up and carry on.

After moving to Connecticut in 1978, I remained active. I walked to High School, walked into the town (deemed a little unusual by my American peers who drove everywhere) and joined the High School marching band, taking part in half time displays at the football matches. I also discovered a love for running, courtesy of Coach Lynch.

I have a very specific memory of a PE lesson with Coach Lynch, in my freshman year, soon after arriving in the US. We were indoors and running around the outside of the gym. He stood in the middle encouraging us and there was some banter that centred around my English accent and the English versus American pronunciation of “water”. I remember feeling good – the running felt comfortable; the banter was funny. Home blood glucose monitoring was still unavailable but my blood sugar levels must have been in the range that they should be and everything just flowed and was effortless – I felt on top of the world.

Mum and Dad had also been bitten by the running bug and, keen to improve their health and fitness levels, had started running. We lived close to a 250 acre park with jogging trails marked out. I found that Sundays, traditionally the least active day of the week, were when I was more likely to feel sluggish and lethargic, most probably as a result of higher blood glucose levels resulting from the reduced activity undertaken. However, these feelings seemed to lessen if I went for a mid-morning run. As a result of still only having urine tests as a method of assessing my blood sugar levels, much of my decision making in these early years of diagnosis continued to centre around how I felt.

I think if you have never experienced the awful physical impact of extended periods of time with out-of-range blood glucose levels, you will find it hard to appreciate just how wonderful it is when your blood sugar is in range for a long period of time. So, running became a form of drug to me. It enabled me to reduce the times my blood glucose levels felt higher than desirable, when no other tools existed for doing so.

My parents entered various “fun runs” in and around Connecticut and I was keen to join in. I am not sure that anyone ever helped me think about what to do with managing type 1. My performance could be variable and I did not participate frequently enough to consider drawing up a plan to help identify what had worked and how I should replicate this in future events. Through the bad days I would just grit my teeth and persevere. However, I had enough good days, that these occasions kept me hooked.

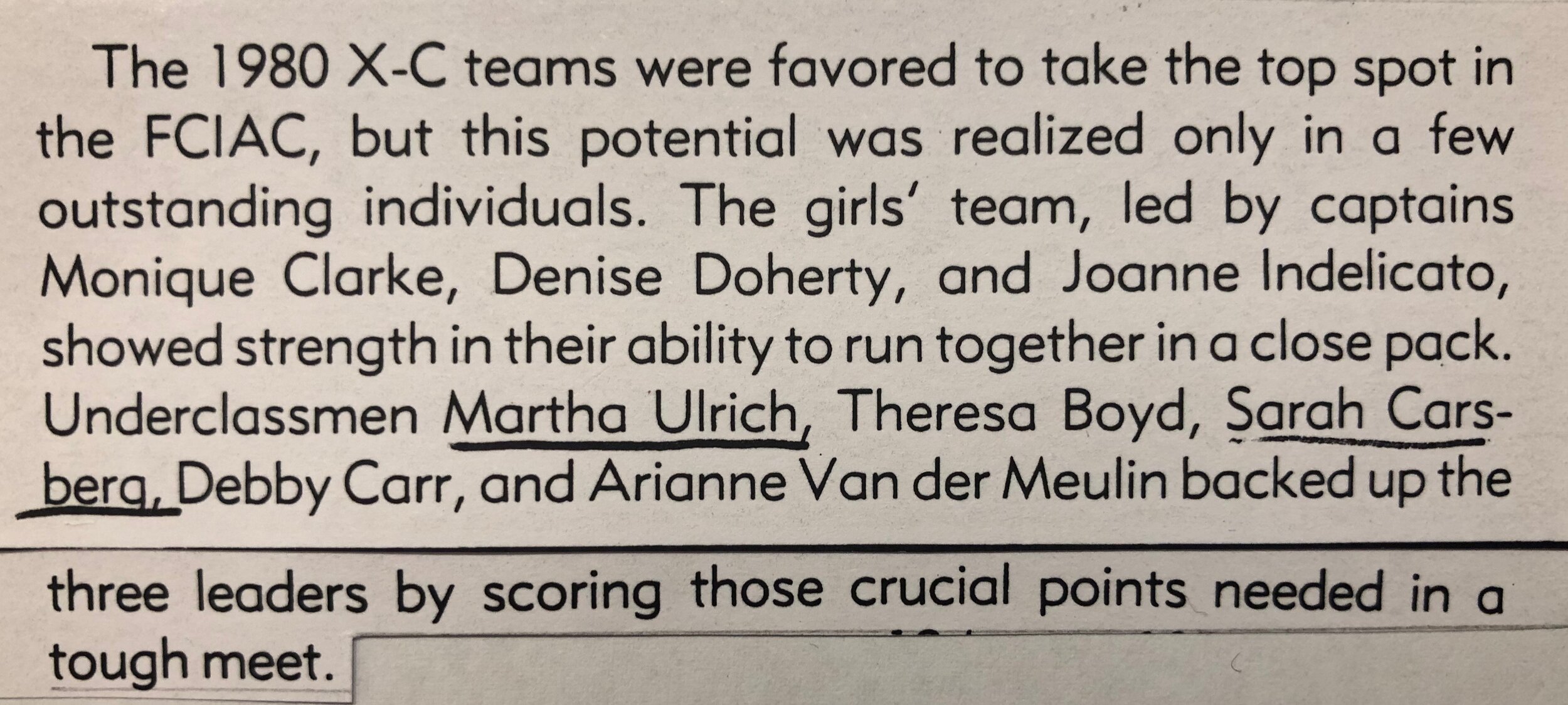

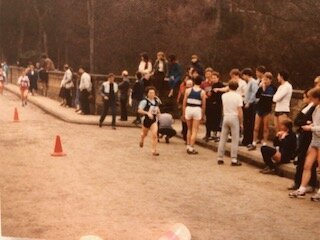

Nine years after diagnosis, in my junior year in high school, when I was taking part in the insulin pump research programme organised by my doctors was the first time that I could start looking at how I might manage my type 1 in relation to exercise. I cannot remember if I was given specific guidance, but I had my first home blood glucose testing machine as part of the research and could identify blood sugar levels pre and post exercise. The pump was large and so I preferred to remove it before running. I found that this worked well – just as my blood glucose levels would be starting to fall due to the aerobic exercise, the lack of background insulin would help to offset this, reducing the frequency or severity of hypos. I found the courage to believe I could be part of a team and joined the high school cross country team. A reasonably solid performer, I was awarded a varsity letter at the end of the year. I still have my letter and it is still hugely important to me. It represents the first time that I felt able to fully participate in a competitive team sport and, although I still had to undertake many decision processes that would not need to be considered by non-type-1s, the condition did not get the better of me.

Running suited me. I continued to run after our return to the UK and could choose how and when to participate to fit around my type 1. I could participate as an individual and fun runs were taking off in the 1980s. We relocated our UK base from Handforth to Guildford, and I found that I could enter various road races there, with my parents. I still removed my pump when exercising. Most of the time I ran distances of between 5k and 10k. I did a couple of longer races between 10 miles and half marathon and although my blood sugar levels would be slightly higher at the end of these, because I had had no background insulin for the duration of the race, this could be easily corrected once I reattached my pump.

When I went to university, I joined the cross country team. The finishing place of each member of the team would be crucial to the overall result, and, if all went well, I would continue to be a solid performer contributing to the teams placing. If I was having an off- day, the higher places of others in the team made me feel that I could forgive myself for my disappointing performance and I would not feel so guilty about whether I had let others down.

With full-time work, pregnancy and then combining a young family with work, my ability to put aside time for exercise was limited for a number of years. I continued to walk whenever I could, walking the children to and from nursery and then school.

After a number of years without an insulin pump, I managed to obtain one again. I restarted running when the children reached junior school and also undertook various all-day walks with family in Shropshire and friends closer to home. I found once again that trying to avoid hypos was difficult.

Appreciation in the medical community, of the difficulties faced by those living with type 1 in determining how best to manage exercise, was increasing but there was still no easy access to guidance and advice let alone solutions. Many of these difficulties were identified by Lumb and Gallen (2009)². They concluded that:

Hypoglycaemia is frequent during endurance exercise.

Hypoglycaemia is likely because, whereas insulin levels fall immediately in a person without type 1 when endurance exercise begins, insulin levels cannot be lowered quickly enough at the start of exercise for a person with type 1. In fact, insulin levels may rise if a site where an injection has been previously administered is being exercised.

Glucose production from the liver may not increase adequately to cope with the increased fuel requirement, provoking the risk of hypoglycaemia.

Hypoglycaemia can be difficult to detect during exercise, as many of the symptoms of hypoglycaemia are sensations that are normal to an exercising athlete.

Diabetes professionals do not feel confident in advising patients on how to manage their diabetes in this context.

A search of the internet led me to www.runsweet.com and, more importantly, to a research study entitled “Managing insulin pumps for exercise (Study 3)” being undertaken by Dr Alistair Lumb who was actively recruiting participants. I signed up.

This research required a significant time commitment from participants: we each had to make five visits to the Human Performance Laboratory in Bucks New University, High Wycombe, which, following the first assessment visit required a commitment of 3 hours per visit. I clearly remember my dilemma at my first visit. I was taken completely out of my comfort zone with the VO2 max assessment. Until then, I had always removed my pump whenever I went running. However, now, based on the anaerobic as opposed to aerobic impact of the exercise and the likelihood that my blood glucose levels would increase as a result of the test, I was advised to keep my pump on and reduce the background rate of insulin. Given that my only experience of exercise in what was almost forty years of diagnosis, involved falling blood glucose levels, I found it hard to trust being told that I was unlikely to hypo and would benefit from having a reduced level of background insulin administered throughout. Showing huge understanding of my concerns and experiences to date, the research team agreed that I would undertake the VO2 max with my pump removed. I started the assessment with a blood glucose in the normal range around 5 mmol/l and ended with a blood glucose of 9.7 mmol/l.

I relished these visits to participate in this research, the sharing of knowledge and ability to spend time learning so much about current thinking in an unpressurised environment, when there was no requirement to stick to rigid appointment times. I felt very bereft when my participation came to an end. Spending several hours in a controlled environment seeing the impact of reducing background insulin by different percentages for different lengths of time prior to commencing one hour of exercise and the resulting impact on my blood glucose levels was interesting and instructive. The renewed confidence it gave me to experiment on myself away from this environment was very valuable.

One of the difficulties with a long-term diagnosis seems to be that a lot of Health Care Professionals assume that, if your annual blood test results are in a range that they are happy with, you will be managing all aspects of the condition satisfactorily. They feel then that nothing needs to be changed. As a patient, it is easy to stop asking whether there are better ways of managing particular situations. So rather than keep asking questions, you just continue to struggle on with the way you have always done things.

Despite the greater understanding, exercise can still be a difficult area to manage.

Following surgery to treat a meniscus tear, my days of running are on hold. I satisfy myself with a brisk 45 minute dog walk, 5 or 6 days a week, undertaken before breakfast. With no on-board insulin and a background rate of insulin that recognises this as part of my daily routine, I am rarely bothered by hypos during these outings. Non-routine or spontaneous exercise can still cause issues.

One of the most frustrating situations to manage is going out for a walk after a family gathering for lunch. A bigger lunch and a pudding will need a higher insulin dose to prevent a high blood glucose spike after eating. However, if this is followed by a walk within several hours of finishing eating, you can be certain it will lead to a hypo, as even gentle exercise increases insulin sensitivity. Perhaps the solution is to inject less insulin with your lunch. However, in the intervening period between finishing lunch and starting the walk, you have to sit and feel increasingly rough as your blood sugar levels climb quite rapidly into double figures. So, do you suggest a walk straight after finishing lunch, having reduced your insulin dose, so that you are exercising before blood glucose levels have a chance to climb significantly? Everyone is likely to suffer indigestion, as food hasn’t had time to settle and the enjoyment lessens with spontaneity removed in favour of a more regimented approach to allow you to accommodate your type 1. So having a pack of glucose tablets in my pocket that I can eat whilst out on the walk, according to need, is the current compromise.

I often think back to the various coaches that I had contact with throughout my youth. It didn’t matter what level of ability individuals displayed. As long as you showed commitment and a willingness to pick yourself up and carry on when you had a bad day, your participation was welcomed. There was a focus on wanting you to be the best you could be without negatively judging individual performances. Much of this mindset has helped me live with type 1. I still have good and bad days after nearly 50 years and I sometimes need the same resilience to keep picking myself up and carrying on.

I refuse to fully give up on the idea of a return to running. I need to find time in my currently busy schedule to identify and undertake appropriate exercises to try to strengthen the necessary muscles. I then need to rebuild my fitness slowly to be able to cope with the physical demands of running. I am still pulled towards it by the sense of empowerment I remember feeling when everything on the type 1 side worked as it should. Hopefully one day.

Notes:

Hypoglycemia is the medical term for low blood sugar. With insufficient glucose in the blood, there is not enough energy for the body and brain to function properly. Hypos require prompt treatment and if left untreated can cause serious problems

“Diabetes Management for intense exercise” – Alistair Lumb and Ian Gallen

Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity

April 2009 – Volume 16 – Issue 2 – p150-155: my summary