24 weeks and counting: Hypos and Hypers - Walking the Tightrope

Understanding the basics

Living with type 1 diabetes requires you to manage your blood glucose levels with the aim of keeping them as close to normal as possible. There are many reasons why this is important. In 1993, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed that participants who had kept their blood glucose levels close to normal greatly lowered their chances of developing complications¹.

Hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose level) is a result of insufficient insulin to process the sugar in the blood. Over many years, high blood glucose levels can cause damage to your body. Complications fall into two categories – macrovascular (damage to the large blood vessels of the heart, brain and legs) and microvascular (damage to the small blood vessels affecting the kidneys, eyes, feet and nerves). A severe lack of insulin in the body can also lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)². This means the body can’t use sugar for energy, and starts to use fat instead. When this happens, chemicals called ketones are released. DKA is life threatening if it is not treated fast.

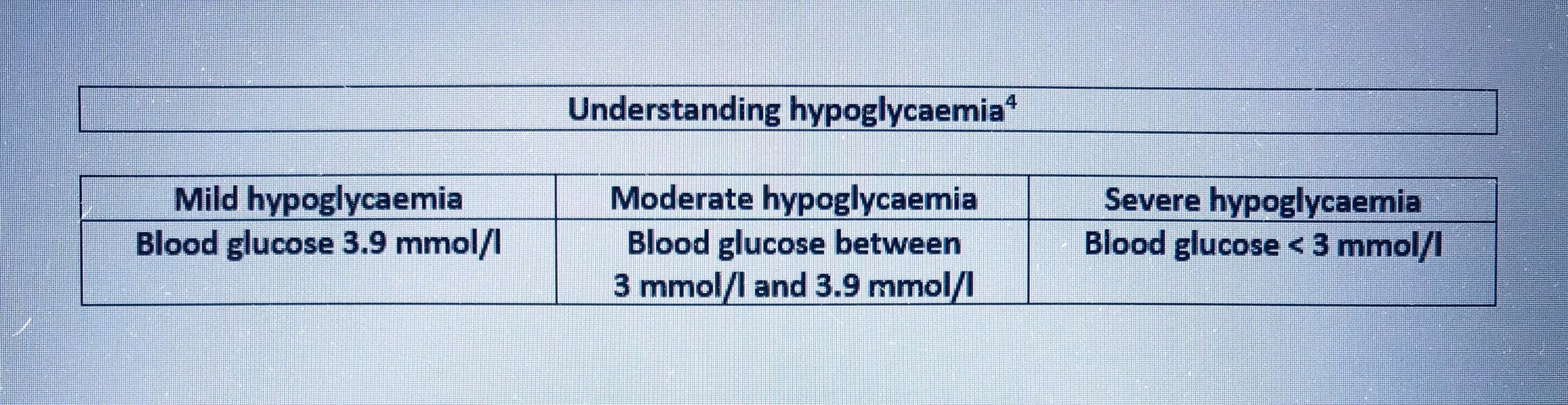

Hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose level) can lead to a range of problems with your central nervous system. Your body needs glucose to function and prolonged low blood glucose levels will lead to a range of difficulties in performing even simple tasks. Gary Scheiner explains that “low blood glucose is usually defined as a level of less than 3.9 mmol/l. Mild lows can cause inconvenience, embarrassment, poor physical and mental performance, impaired judgement and mood changes. Severe lows can induce seizures, loss of consciousness, coma, or even death³.”

There are many opinions on what an appropriate blood glucose target should be. The Diabetes UK website suggests you aim for a reading of between 4 and 7 mmol/l on waking and before eating. After meals, blood glucose levels should be in the range 5 to 9 mmol/l. These targets will be a general starting point and then, depending upon your age and specific circumstances, your health care team may recommend adjustments⁵.

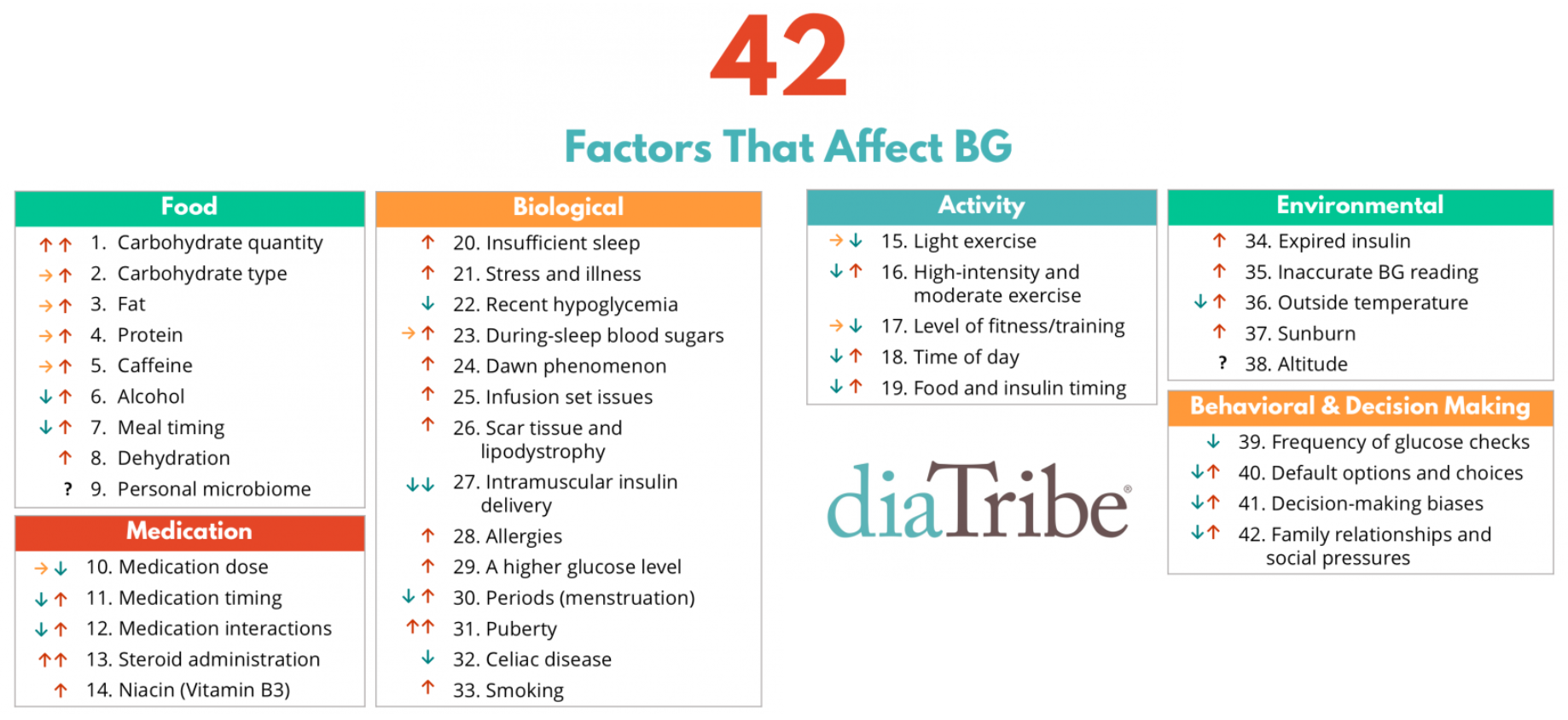

Maintaining in-range blood glucose readings is a difficult process. Adam Brown summarised forty-two factors that can affect blood glucose levels: he based his conclusions on his personal experience, conversations with experts and scientific research⁶. How your body responds to daily life does not remain constant. Even if you choose to follow a very rigid routine, eating the same food and undertaking the same activity, at the same time every day, you can never be certain that blood glucose readings will follow a previously identified pattern.

So, diagnosis requires you to start on a relentless journey of exploration, learning how best to respond to the results from the monitoring devices you have access to, how best to estimate the amount of insulin to inject, how best to manage food consumption, exercise and other daily activities, in an attempt to ensure that the decisions you make enable you to keep your blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible.

The impact on daily life

Me: Hypos were difficult to avoid in the early years after diagnosis. For the first nine years of my diagnosis, home blood glucose monitoring did not exist. The most sensitive urine test result would indicate whether or not your blood glucose was likely to be below 10 mmol/l (a blue reading). So, a urine test could not differentiate between hypoglycaemia or in range readings. Even if better monitoring had existed, the available insulin was not sufficiently fast acting to be capable of quickly reducing blood glucose levels that were too high.

Dad: Sarah's condition turned out to be quite complicated. In the terminology used at the time, she was classified as a 'brittle' diabetic, because she had so many hypos, the upsetting episodes caused by low blood sugar, despite all the care we took to try to anticipate them and take avoiding action. During the day, her behaviour normally signaled clearly when her blood sugar was falling and we could give her some glucose to ward off the danger.

Mum: It was quite obvious when you were low during the day. You looked different, your eyes showed it by being more glazed, you didn’t speak in the same way and your speech and actions were slowed down.

Me: The physical impact of a severe low felt awful. By the time that either I or others around me were aware that I was low, it was having a significant effect on my ability to feel I could engage with anyone or anything. The worst part was trying to cope with any conversations. I remember that someone’s speaking to me felt like noise that I needed to shut out, to be able to cope with how I felt. I have discussed with Mum how she felt she reacted to hypos, as I always felt that she was panicking when trying to get me to eat something. I think with hindsight my interpretation of her behaviour was more a case that I was unable to cope with processing the instructions she was giving me. I remember feeling the desperate need to stop this “noise” and to shut it out. It is recognised that a severe low blood sugar prevents a rational understanding of what is happening around you.

Mum: I don’t remember panicking about your hypos, except the night time ones. You seemed to me to be very stubborn and obstinate in refusing to admit that you were having a day time hypo, even though it was apparent to everyone else, and I used to get exasperated and at my wits end, trying to persuade you to have a glucose tablet. No doubt it was wretched for you to have to put up with this ‘interference’ and being singled out. I never got the knack of persuading you to take glucose tablets - my temperament, of course, rushing in. Dad, on the other hand, managed an easy tactful approach and you would take them for him, but he was so often not home yet, so it fell to me most times.

Dad: Nighttime was much more difficult. Without warning, Sarah’s blood sugar could plummet either late at night, or in the early hours of the morning (despite all the precautions we might take), and we would waken to hear the headboard of her bed banging against the wall as she had a 'fit' induced by the extremely low blood sugar. We then had to smear her lips and mouth with a glucose paste and try to force her clenched jaw open enough to get some inside her mouth to bring her round. Margaret suffered poor quality sleep for a long time, as she willed herself to be alert for a rapid response to overnight problems. We discussed Sarah’s problems with Dr Price and he told us honestly that the reasons why some type 1s were brittle were not well understood and there was no sure way of avoiding these nighttime hypos. We were advised to avoid the temptation to give Sarah extra carbohydrate to "be on the safe side" because this could cause problems of a different kind.

Deb (sister): The headboard banging would wake me and there were times where I would be the first person to wake to Sarah’s ‘fit’. It was very shocking to witness. On one occasion when Dad was away, Mum found Sarah unconscious and shouted for me to wake up and phone an ambulance. By the time the ambulance arrived the sugar paste had started to work but it left Mum and me very shaken. After this episode there were times when I would wake in the night to listen out for the headboard banging and would get up to make sure that Sarah was okay.

Mum: Dr Price was truly puzzled by your nighttime hypos and fitting, and told us so. He was on the point of referring you to Great Ormond Street when the American trip came up. He was delighted to be able to refer you to Dr Tamborlane at Yale whom he knew from attendance at conferences.

Me: Having been invited to participate in Dr Bill Tamborlane’s early insulin pump research at Yale University Medical School, I gained access to my first blood glucose testing machine in 1980/81. The more consistent delivery of insulin via a pump and the ability to check blood glucose readings at home, especially before bed, reduced the severity of hypos. The blood testing equipment was not portable so checks were still not as frequent as can be managed today but nevertheless it offered greater information to assist with managing the condition.

The US pump and home blood glucose monitoring continued to help with managing the condition on the return to the UK. However, even with say 4, 6 or 8 blood glucose tests a day, if each one took a minute and gave you knowledge of what your body was doing at that precise moment, that could still leave around 23 hours and 50 minutes every day, where you would have no detailed knowledge of how your body was responding to daily life. So, although I generally felt the symptoms of a high or low blood glucose level, if I was not specifically focusing on these feelings, perhaps because I was surrounded by other people, conversation or activity, or gripped by a programme on television, a play at the theatre or just general daily life, I did not always register the gradual rise or fall in blood glucose levels.

Although the absolute value of a blood glucose reading partly determines how you feel, my experience is that the speed with which my blood glucose levels change determines how quickly I pick up on the symptoms of a high or low blood glucose level.

Neil (husband): I can’t remember the first hypo I witnessed but I do remember looking out for the tell-tale signs. You would switch off from what was going on around you – conversations or television programs. The problem was that sometimes this was just tiredness as a result of commuting to work in London, studying for an accountancy qualification in the evenings and renovating a house at the weekends. However, when you were hypo, I did also notice that your thumb would start to twitch.

Me: I always find it easier to treat a hypo when I am on my own. I am fiercely independent and hate feeling that those around me are thinking that I should have worked out how to avoid these problems by now. Eating glucose tablets or drinking juice when others are around, particularly close family who know that I am likely to snack only when low, will draw attention to the issue. Huge misunderstandings still exist regarding the complexities of managing the condition. Many people believe that if you follow the rules, you will not experience problems. Type 1 diabetes has yet to be told what the rules are!

I have been aware of my difficulty in acknowledging hypos to close family and I have tried to search for a solution. I suggested that, when Neil was aware that I was low, he should say that he was hungry and wanted a biscuit, so that he could offer me one too. The likelihood was that I had been sitting there, trying to decide on the best time to interrupt what we were doing and whether to say something. Although biscuits are not the best treatment for a low blood sugar, it was a way of helping me to ‘save face’, feel less of a failure and to treat the hypo. This is an area I continue to work on.

Izzy (daughter): The biscuit tin leaves a strong memory. My brother, Tristan, was out at a friend’s house for a sleepover and the three of us were watching the Eurovision song contest, snuggled up under the duvet in your double bed. I think I must have been about seven years old. I don’t recall how events unfolded but I remember being delighted by the fact that I suddenly had a whole double bed to myself and an unsupervised biscuit tin in the middle of the bed. I knew that something was going on because neither of you were paying much attention to the television and you had retreated to the en-suite in a bit of a daze, but I was too young to really understand what was happening or to find it worrying. I feel that you were probably trying to hide the hypo from me in the en-suite until your blood glucose had returned to normal, but you need not have worried as nothing could tear me away from the Eurovision song contest.

Me: Hypos are a regular part of life with type 1. Even with more reliable and frequent monitoring, you have to accept that a narrow margin stands between a normal blood sugar level and a hypo. NICE guidance states “most people with type 1 diabetes have hypos quite often. Most hypos are mild, but some can be severe, which means that you need help from someone else to treat the hypo. The fewer hypos you have, the better.” ⁷

Neil: I have had to intervene to help Sarah only a couple of times in the last thirty years. Two occasions were overnight hypos when she was still in the early stages of breastfeeding Tristan. It seems that far more guidance is available to type 1 mothers today than when Tristan was born in January 1995. There was no advice given to her on the importance of carbohydrate replenishment when breastfeeding and with hindsight we can now see that we should have realised the energy demand being placed on her body and thought to keep a supply of juice cartons or biscuits within easy reach, to help cope with the impact that feeding had on her blood sugar. However, it is easy for self-care to be overlooked when you are adjusting to parenthood.

When our ante-natal group met up for dinner, several months after all the babies had been born, Sarah had planned her mealtime injection to coincide with the agreed time that food would be served but for various reasons, food was significantly delayed. The occasion was made worse as Sarah had been breastfeeding Tristan for much of the early evening. The antenatal teacher was able to locate a hypo treatment in the form of some mini bags of chocolate buttons that she kept in stock for her children.

Me: Hypos have been more common when I am undergoing either hormonal changes or changes to a usual routine. After a more stable interval following the unpredictable impact of pregnancy and breastfeeding, I found that avoidance of hypos became more challenging again as I entered the perimenopause. I remember the very first perimenopausal hypo that caught me off guard. I was walking our daughter Izzy to junior school and becoming more and more frustrated by what I thought was her inability to walk in a straight line. As we walked side by side, she just seemed to be bumping into me a lot. With a feeling of absolute horror, it suddenly dawned on me that she wasn’t the one with the problem. I was carrying house keys, my mobile phone but no glucose. I had become complacent about carrying glucose with me on the morning walk to nursery or school, as I had not had hypos in the 8 years of doing this. With no glucose to hand, I had to raid her packed lunch. I spent the rest of the day worrying about whether she would have enough to eat at lunchtime or be hungry throughout the afternoon. Since then, I have ensured that I always carry some form of hypo treatment with me, no matter how short the journey may be from the house.

Izzy: I remember walking along the long straight pavement to school with you and you kept walking into me. I didn’t think anything of it at first but then you asked me whether I was walking into you on purpose. I was adamant that the collisions were not my fault. I think that’s what made you realise that something was wrong but you always just dealt with issues quietly by yourself without making a fuss. Apparently, you stole a Kitkat out of my lunch box but I really don’t remember that.

I think that, when you became concerned that you were experiencing more hypos, you must have sat down and explained things to me and Tristan. You kept a squeezy tube of sugar paste in the top drawer of your bedside table. Because Dad left for work before the rest of us had to get up, you explained that if we woke up and didn’t hear that you were awake, we needed to wake you up. If we couldn’t, we should call for help and squeeze the sugar paste into your mouth. I remember being quite surprised because I never thought that type 1 would lead to anything so serious. I felt very concerned for a number of weeks after this talk. Whenever I woke up, I would lie in bed for a moment to double check whether I could hear any sounds of you in the shower. There was one Saturday morning when I was confused about what day of the week it was. Thinking it was a school day, and worried that there were no sounds coming from your room, I went to wake up Tristan as I was too scared to go and investigate on my own. Fortunately you and Dad were just having a lie in.

Tristan (son): I have very few memories of any specific hypos. When we arrived home from school, you would generally chat to us about our day, homework and what you were making for tea. Whenever you were less talkative, it would often suggest that your blood sugar might be starting to go low. We kept a supply of jelly babies in a cupboard and Izzy and I had been told that we could not help ourselves to them because they were hypo treatments. I remember offering to get them out of the cupboard on a few occasions if I thought you might need one. I thought the offer of help would make it more likely that I would be allowed to share in the stash of jelly babies with you. (I was more than happy to take one for the team!)

Neil: After a two year battle, you finally had funding approved to receive an insulin pump in 2010. This has helped to reduce the severity of the many swings in blood glucose that you were experiencing as a result of the perimenopause. A bigger advance though is the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) you started using in 2014. Even though we have to self-fund, the benefit you get from the constant readings on your phone and the ability to head off lows or highs, with the micro dosing of food or insulin, before they become too problematic, is priceless.

Me: Even with all the technology to help, significant changes to my daily routine can still lead to highs or lows. One example arose when we had a family holiday at Lake Maggiore, Italy, and spent a day out travelling between the islands on the lake, sightseeing and enjoying specialty biscuits, chocolates and ice cream as we wondered around. With hindsight, I can see that I gave myself too many small insulin doses to cover the carbohydrates being eaten, at intervals that were too close together. The insulin doses seemed to be managing the food intake well, until they weren’t. I had chosen to run blood glucose levels at the slightly higher rate of 8-10 mmol/l for the day, to cope with the different foods and walking, which seemed to be working well, until it wasn’t. Giving insulin doses at close intervals can lead to what is described as insulin stacking which is eventually likely to cause a hypo. We stepped off the final ferry and my blood sugar levels started to plummet. I remember feeling very disengaged as I followed the rest of the family into a restaurant for dinner. I was surprised by the speed of blood glucose drop and it was one of those hypos that glucose just seems incapable of correcting quickly. It was the sort of low that makes you want to devour every item of food in sight. It was the sort of low that feels so bad that you over-treat it and that causes a rebound high several hours later; but when you are so desperate to correct the feeling you find it difficult to be moderate in your treatment.

Izzy: The only hypo I remember clearly, because it was the only one that I was aware caused a dramatic change in your behaviour, was the one when we went to Italy in the summer after my first year of university. We had taken various boat trips, hopping between small islands situated off the coastline where we were staying. On our return, we went into a pizza restaurant for dinner. I can’t remember the exact moment when I realised something was wrong – it had been a long day and I just assumed you were quiet because you were tired and hungry. However, Tristan told you a joke and you didn’t acknowledge it at all – although to be fair, that is not an unusual reaction to Tristan’s jokes! Instead, you just sat there looking mildly confused and I remember feeling you were looking around as if you were not sure about where you were or what was happening. I think it is the only time I have ever felt you look at the family and not fully register who we were. Dad kept passing you more bread to eat until the pizza arrived. As you started to re-engage with what was going on around you, you got more sugar out of your bag to eat and slowly returned to normal. I remember your saying that you had no memory of what had just happened.

Me: The decision to self-fund the CGM since July 2014 has helped enormously with being able to monitor trends in my blood glucose levels and act upon high or low readings that look like they will lead to extremes if left unchecked. Much as I would love not to experience either state, I find it generally easier to raise a low blood sugar than reduce a high blood sugar. I worry about the long-term complications that can arise from high blood glucose levels and as a result recognise that I might sometimes be a little heavy handed in insulin dosing to return rising blood glucose levels to normal. Although use of technology does not enable complete avoidance of highs and lows, their severity has lessened considerably since the early years of diagnosis. This does however come at a price. Whilst the NHS is unable to afford the provision of CGM to all those diagnosed with type 1, and whilst I remain in employment and able to pay the monthly charge, I will continue to self-fund a CGM. Part of the cost is a non-financial one. For all the benefit the CGM brings, its use involves keeping watch over the patterns of my blood glucose levels, and coping with interrupted sleep from overnight alarms alerting me to levels out of range. You are never allowed time off from the condition. At times, it can feel completely overwhelming.

Notes

1. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) website

Blood Glucose Control Studies for Type 1 Diabetes: DCCT and EDIC

viewed August 2021, my summary

2. Diabetes UK website, viewed August 2021, my summary

Hyperglycaemia (Hypers)

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/hypers

What are the signs and symptoms of DKA?

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/diabetic_ketoacidosis

3. Scheiner, Gary 2011, Think Like a Pancreas: A Practical Guide to Managing Diabetes with Insulin, p220, Da Capo Press, Boston.

4. JDRF website, viewed August 2021

Low Blood Sugar: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment for Hypoglycaemia

https://www.jdrf.org/t1d-resources/about/symptoms/blood-sugar/low/

5. Diabetes UK website, viewed August 2021, my summary

What’s my target range?

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/managing-your-diabetes/testing

6. Brown, Adam (author) and Close, Kelly (foreward) 2017, Bright Spots & Landmines: The Diabetes Guide I Wish Someone Had Handed Me, The DiaTribe Foundation

7. Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management

NICE guideline (NG17), Published: 26th August 2015; Last updated: 21st July 2021

Viewed August 2021