12 weeks and counting: Family and Friends

“Any chronic illness carries the potential to impact on the life of the family….

Family members suffer greatly from the emotional effects of living with, and caring for, a relative with a disease, with the impact of some diseases being felt by every member of the family…. The psychological distress felt by family members often results from their feelings of helplessness and lack of control. Many different emotions are mentioned by family members: guilt, anger, worry, upset, frustration, embarrassment, despair, loss, relief. Each emotion affects family members in different ways and to different extents, often depending on the disease severity of the patient, and the period of time that has passed since the diagnosis.” ¹

Me: Once I was able to return home after my type 1 diagnosis, the health care focus was on teaching us about the physical side to managing the condition. No support was offered to me or my wider family, to help us all come to terms with the many emotions experienced. My parents had to learn as much about the condition as they could in a very short space of time, in an era when very limited information was available in the public domain.

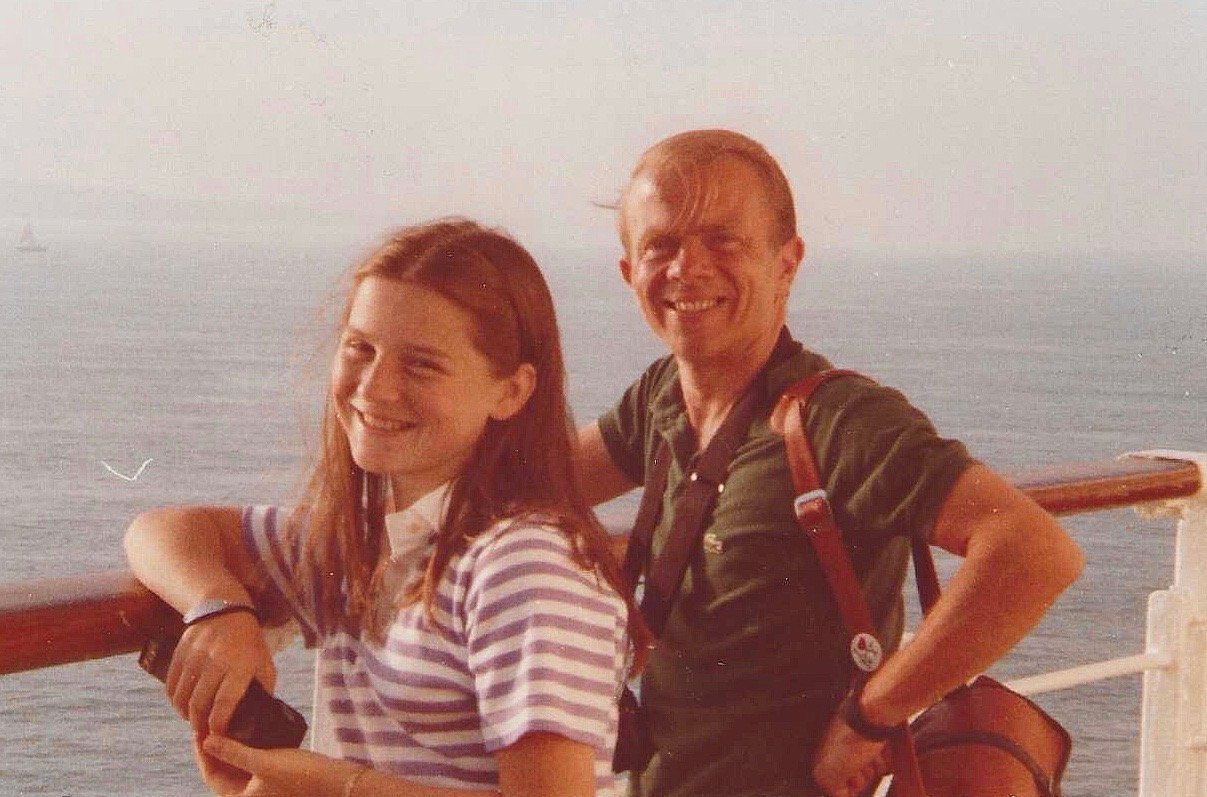

Dad: Once home from hospital, as we gained experience, we also quickly came to see that having a positive attitude was important. We tried to take the view that Sarah could do everything that a child without diabetes could do. We would not accept any restrictions: everything was possible.

Me: Just as my diagnosis had a huge impact on me, it also had a significant impact on my sister Debbie. It was difficult for her to witness the traumatic situations that occurred both at diagnosis and with the overnight hypos that I experienced. I am sure that she sometimes resented the impact that my diagnosis had on family life as much as I did. As an adult, I have heard the parents of children diagnosed with type 1 in recent years state that they feel sorry for the effect that the diagnosis can have on siblings and for the lack of formal support available to help youngsters and the family process these events.

Deb (sister): The overnight hypos had a significant impact on me, especially after being the first person to find Sarah fitting one night, after waking to hear her headboard banging against her bedroom wall. I felt responsible for helping to keep Sarah safe and so for a long time, I would regularly get up in the night to check that she was okay. Even when I felt very tired, I knew I could not forgive myself if I hadn’t checked to see that she was not experiencing a bad overnight hypo.

The injections were the earliest and most obvious change in daily life at home. The practising on oranges, then herself and the tense atmosphere at injection time made me feel very helpless. Apart from admiring Sarah’s courage, I knew there was nothing I could do to help, so I tried to stay ‘out of the way’ to avoid adding to the tension. I also felt guilt at being the ‘well’ child, when so much of Sarah’s life had changed. The diagnosis impacted virtually every aspect of family life while we all adjusted to the new normal.

Me: I was grateful in my pre-teen years, that my sister often provided a very re-assuring presence both on our bus journeys to and from school and in school itself. Although she could not have done much in medical terms, knowing that she was nearby gave me a greater feeling of safety. I remember one occasion when I was sent to the sick room at school and the office staff pulled Debbie out of her class to come and sit with me, until Mum was able to collect me. Debbie bought a book with her that they must have been studying and she read it aloud to me. I felt too ill to be able to do anything other than curl up on the bed but her reading to me gave me a sense of security.

I do feel that my parents’ early approach and attitudes stood me in good stead for a life with type 1. The age at which I was diagnosed and the changes made to family routines to help accommodate the very unsophisticated treatment in the 1970s, meant that I was not really aware of the rigid impact on lifestyle. I lived the routine, believing that our general lifestyle was no different from that of anyone else.

I had certain frustrations – entering adolescence and feeling that I couldn’t express normal teenage angst without being asked “was I hypo?” When my behaviour was the only way of detecting hypoglycaemia in those first eight years of diagnosis, concern about whether I was hypo was an understandable response but one that led to even greater feelings of frustration. However, I was not aware when negotiating boundaries with my parents, that type 1 was ever a consideration for what I was or was not allowed to do. The condition therefore has never made me feel that I should adjust any of my life choices, (I just need to have factored in the potential impact of type 1) and for that, I am very grateful.

Mum: As I look back on your childhood, I don’t remember feeling particularly stressed by the management of your type 1, except for the time when you were having night-time hypos, and fitting, which was stressful and actually had the effect of disrupting my own ability to sleep, because I was anxious to be alert in case you had an episode. We established a family routine shortly after your diagnosis and this quickly became part of normal life. One of the most worrying times for me came later, when you moved into a flat. I worried about you living on your own and about what might happen if you had a severe hypo with no-one around to help you. What a help it would have been, if you had had access to mobile phone and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology.

Neil (husband): I first met Sarah in April 1989. We had both been attending the same accountancy training course, paid for by our respective employers, leading to the first stage of professional ICAEW examinations. She had undertaken blood tests at her desk when necessary. She didn’t hide her type 1 diabetes or apologise for the tasks that she needed to undertake but just got on with them. She was still wearing the American insulin pump and it was a large enough piece of technology that it could not easily be ignored.

I plucked up the courage to ask her out. There was no reason to consider type 1 in that decision. She had been living with it for seventeen years and I had only just got to know her and knew next to nothing about the condition. I don’t remember asking much about it in those early days or ever seeing her experience hypos or hypers. She was fiercely independent and got on with making the necessary management decisions around any plans that we made.

Me: I don’t think it ever really occurred to me to sit down and talk to Neil in detail about type 1. I didn’t remember much about life pre- type 1. I didn’t hide anything and was happy to answer any questions but it was such a normal part of my life, it was easy to overlook the fact that my normal was not Neil’s normal. I also didn’t want to be treated differently. I had been living away from home for some time and had assumed sole responsibility for the management of my type 1 for seven or eight years. I was not looking for a carer.

Neil asked me to marry him just over a year later. My engagement ring was spotted at my next diabetic clinic appointment. I was told about the importance of tight management of blood glucose levels if I planned to have a family. I was also told that it was the current recommendation to have any children before the 25th anniversary of diagnosis. Pregnancy put greater pressure on your body and if you had any early signs of type 1 complications, pregnancy could lead to their worsening.

I abandoned the pump and returned to multiple daily injections (MDI) before the wedding. I understand that insulin pumps went through a phase of falling out of favour and my now 10 year old American pump, with an original warranty of 2 years and supplies that I was paying to import from America, was not going to be easily accommodated under a wedding dress! I moved onto a minimum 4 injections a day routine, using insulin pens.

Neil and I both wanted a family and, knowing about the increased risks with type 1, I undertook considerable research to try to pin down the issues more exactly. I obtained an information pack from Diabetes UK. I scoured all the pregnancy sections in bookshops, reading any relevant chapters on type 1 and pregnancy – there weren’t many! I spent three months taking folic acid, cutting out alcohol and planning and testing a repertoire of meals with appropriate insulin doses. My aim was to have tighter management of insulin dosing in a non-pregnant state to allow greater confidence at recognising the impact of hormonal changes on blood glucose levels and how best to manage them, once pregnant. I was going to have complete responsibility for another life and I wanted to ensure that I could do everything within my control to give our baby the best chance of coming through a type 1 pregnancy unscathed.

I was excited to conceive very quickly and, to the surprise of many, I didn’t wait to tell family. For me, the pregnancy had effectively started three months before the positive test result with the very strict care I was taking over managing both my general health and type 1. I told my diabetes clinic at Guy’s hospital almost immediately. The posters in clinic made it very clear that I should share information as soon as it was available. Over the following 8 months, I had very frequent appointments scheduled every few weeks with both the type 1 and antenatal teams. Management of the pregnancy was tough. The hormones in pregnancy make blood glucose levels increase and, by the end of pregnancy, insulin doses commonly need to be 2 or 3 times higher than they were pre-pregnancy. I could not find any guide to help me determine at what point in the pregnancy, dose changes were likely to be needed. I tested blood glucose levels regularly. Given the need to try to understand how my body was behaving over a 24 hour period, I would frequently undertake between 20 and 24 blood tests a day when trying to determine the increases in insulin dose required to cope with the changing pregnancy hormones.

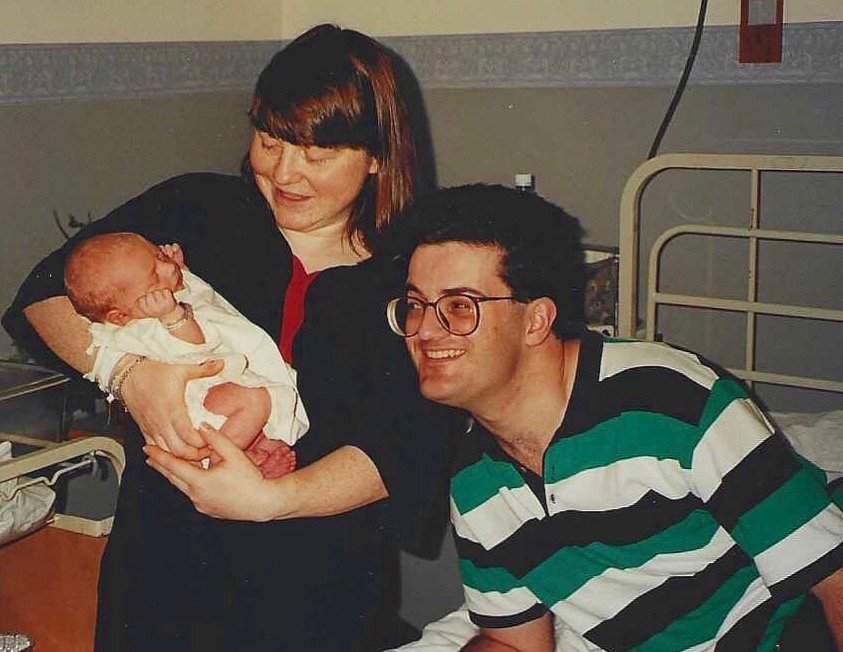

At 39 weeks gestation, I was admitted to Guy’s Hospital for an induction and trial of labour. It was recommended that type 1 pregnancies did not go past their due date, in order to limit what was an increased risk of still-birth for type 1 mothers. My trial of labour ended with a caesarean section and Tristan was born in early January 1995. I have strong memories of being asked if I wanted him to be given glucose or formula to treat any low blood sugars post birth. I was adamant that I wanted to breastfeed him and so would agree to decide on special measures to counteract low blood sugar only when absolutely essential. My sister, a trained breastfeeding counsellor, had helped source information on the benefits of breastfeeding babies born to type 1 mothers. The midwifery team were very supportive. Tristan had a mild low blood sugar at birth but he stayed with me and I fed him on demand. The midwives tested his blood sugar before each feed, pricking his heel to obtain a tiny drop of blood and by the following day, his blood sugar levels had started to stabilise.

Fifteen months later, having successfully managed one pregnancy with type 1, I felt more confident embarking on a second one. As with Tristan, I spent 3 months making sure my general health and type 1 management was as tight as it could possibly be and again became pregnant very quickly. I was now working part-time and I was planning to take a career break after this birth, so Neil and I decided to sign up for antenatal care at the local hospital. I was booked in for an elective caesarean about four days before my official due date and Izzy was born in April 1997 – 25 years and one month after my type 1 diagnosis.

Pregnancy with type 1 is hard. I had spent 12 months with each pregnancy imposing strict regimes on myself, including tight dietary control, to reduce the risks that would be caused to the baby, by out-of-range blood glucose levels. After a year of such tight management and significantly higher insulin requirements, it was sometimes difficult to remember that I could ease off maintaining quite such rigid control. Insulin requirements plummet immediately after birth and so it was important to be careful with insulin dosing to recognise this.

In an ideal world, postnatal care should be able to offer the mother and baby the continuation of care that was necessary throughout pregnancy until they are discharged from hospital. I was well supported by the midwives at Guy’s Hospital who, I felt, cared for me and Tristan as a family unit post birth. They made sure that I understood all of the checks they performed on Tristan and shared his results with me. When checking his blood glucose levels, they would make sure that I was also okay and offer any necessary support.

This was very different from the post-natal care after Izzy was born – I felt that the midwives were focused on her and had no understanding of the help or support that I might need in managing type 1 with a new baby. Izzy fed constantly in the first twelve hours after birth. I was not focusing on myself and failed to consider the impact that Izzy’s feeding was likely to have on my blood glucose levels. Outside routine hospital mealtimes, no additional food was available to me as a breastfeeding mother with type 1. Izzy became quite unsettled and grizzly as that first evening progressed, and around midnight, a midwife came and took her away to the nursery. I find this awful to reflect upon. I wanted to keep her with me, I am not sure whether anyone invited my views on the plan but, if they did, I must have appeared tired and confused about what was happening. I obviously put up no resistance.

A midwife returned Izzy to me the following morning. The interaction the previous night must have raised questions in her mind, as she asked if I had been hypoglycaemic when Izzy was taken. The sequence of events started to make sense to me but did not make me feel good about myself as a mother – even though there was little that I could have done without having the appropriate support and treatment provided by medical staff. The recognition that no-one had sufficient understanding of type 1 to be looking out for me has just reinforced my belief that my diagnosis of type 1 will always require me to be in complete control. I cannot afford to rely on others.

This episode had a critical impact on both my willingness and confidence to seek help, if I felt that I was having management difficulties with my type 1, in my early years with the children. Although, perhaps, it was not a rational reaction, a part of me was always slightly worried about admitting to hypoglycaemia when the children were younger for fear that they would be taken away from me.

I have been interested to understand, now that I have children of my own, how both family members and friends see me and whether they feel that my diagnosis has caused health concerns for themselves. The majority of people in my life have never known me without type 1.

Deb (sister): I have tried to use Sarah’s diagnosis to help inform friends about type 1 and the problems that the condition can cause. I didn’t spend time worrying about developing the condition myself or whether my own children would be at greater risk of developing the condition. Sarah’s coping strategies show that it is still possible to lead a full life.

Izzy (daughter): I remember I went through a phase of hiding my eyes every time you did an injection in the morning before breakfast. I think it was when I was still at infant school and just beginning to understand that you were putting a needle into your skin. It wasn’t that it upset me to see you do it to yourself, as I knew no different. I just didn’t want to think about ever doing it to myself, so preferred to pretend that it wasn’t happening.

I don’t think I ever really understood the impact of type 1 as the medical kit and practical management considerations were always a part of daily life and all I had ever known. I started to appreciate the impact only when I went for sleepovers at friends’ houses. I remember eating dinner with the whole family and would find it strange when their mums would just sit down and start eating. I found it even more strange when we would have a pudding and they would eat it without having to think about how high their blood sugar was and whether they needed further insulin to prevent blood sugar levels skyrocketing. That made me realise how different life was for you.

It used to annoy me that you had no sympathy for the trauma of vaccination days at secondary school. I never liked needles but didn’t make a huge fuss about the process of being vaccinated as seeing injections performed was a normal part of everyday life. However, teenage me would have liked some “bragging rights” about how sore my arm was or how long the needle was but it seemed not to be appropriate, given what you had to put up with, and so I had to find a sympathetic audience elsewhere.

I don’t think I have ever been seriously worried about being diagnosed with type 1. You have always made sure that Tristan and I know the symptoms, just in case. Everything that you did each day to manage the condition has been a very normal part of our lives. I appreciate that we only ever saw the obvious visible signs of the condition and not the difficulties associated with managing type 1 but I think that, when I was younger, I assumed that if I was ever diagnosed I could do just as good a job at managing it as you. So, there was no need to worry.

Tristan (son): I think the most notable consequence of your type 1 for me was the lack of sweet things in the house. I always enjoyed going round to friends’ houses for the novelty of having dessert after dinner, or fizzy drinks. I was occasionally embarrassed about not being allowed Coco Pops, for example, and sometimes secretly/ swiftly put a spoonful of sugar on my Weetabix before anyone saw (it was a quiet revolution). I stopped doing that when I realised no one else had touched the bag of sugar in years, and if someone came to it half full in the future, I would be the prime suspect.

The actualities of your day-to-day never really bothered me, though, besides being sad that you had to do it, and being grateful that I didn’t. I never felt embarrassed because it was never made to be a secret, and never something you seemed to be embarrassed about. If a friend of mine asked me what you were doing, I’d quite gladly tell them. I realised, of course, that it wasn’t ‘normal’, but your management was so skilful that it never really impacted my own life, besides apologising to friends who stayed over that they couldn’t have fun cereal.

Unlike Izzy, I never minded vaccinations or needles, but I do remember a few times you had suggested we should try testing our own blood sugar levels using your old kit. I really didn’t like pricking my finger and tried to switch off from it when I saw you doing it so many times a day. It was because of that, that I felt so invested in your attempts to gain funding for a pump.

Katie (friend): I think you will be surprised by the impact your type 1 has on your friends. I have only been really concerned about your type 1 on one occasion when you were on the phone to me and were obviously having a hypo. Tristan and Izzy were only little and I wasn’t sure if Neil was home. I hung up, immediately rung back and was so relieved when Neil answered the phone. The fact that I was too far away to offer you any practical help should you have needed it, was a huge worry.

Your management of the condition is so skilful that it almost passes me by, however at the same time I am aware that some of those characteristics which I love and admire about you and have resulted in our enduring friendship, are probably as a consequence of your living with type 1 for, as you say, nearly 50 years.

When I was diagnosed with a condition that required daily subcutaneous injections over a period of three months, you coached me down the phone on how to get over the psychological and physical challenges associated with this. As someone with a previous needle phobia, this was invaluable. I also gave myself a strict talking to along the lines that if you could do this every day of your life, then I could certainly do it for 3 months. I still occasionally have to do those injections and your coaching tips are in the back of my mind each time.

Neil (husband): In many respects, I have been less aware of your living with type 1 over recent years than I was previously. I put this down to the technology that you now use. The pump and CGM allow small adjustments to be made in managing your day-to-day life before the type 1 starts to cause significant problems with low or high blood glucose levels, so it is less intrusive in our daily life. However, I am also becoming more aware of the condition and its impact as you are becoming more open in talking about it – largely as a result of the positives you have found from linking up with other people in the type 1 community. And talking about it benefits everyone and is not boring!

Dad: Your diagnosis was a life changing event- in the lives of Mum and me, as well as yours, and it needs to be seen as part of our family’s story.

Notes

1. “The impact of disease on family members: a critical aspect of medical care”

Catharine Jane Golics, Mohammad Khurshid Azam Basra, Andrew Yule Finlay and Sam Salek

JRSM – Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Oct 2013, 106(10): 399-407

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3791092/